The increase in wildfires over the last few years have left many wondering if they can trust the AQI ratings. These are meant to tell us if it’s safe to go outside and breathe freely, but ‘clean’ air scores post-wildfires have raised serious questions over how we measure air quality after such tragedies.

What is the Air Quality Index (AQI)?

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) runs and funds the Air Quality Index (AQI) in the U.S. This index measures air quality from monitoring stations across the country and creates an AQI value for any given location.

For our take on monitoring indoor air quality, see this post.

The AQI score is typically included in local weather forecasts and is available online and through an app.

This score runs from 0 to 500. The higher the number, the greater the risk of adverse health effects from poor air quality. To make things simpler to understand at a glance, the AQI categorizes air quality scores into six groups and then assigns each a color.

In the U.S., the colors are:

- Good (Green): AQI 0-50

Air quality is satisfactory; air pollution poses little or no risk to health. - Moderate (Yellow): AQI 51-100

Air quality is acceptable, but some pollutants may cause concern for a very small number of people who are unusually sensitive to air pollution. - Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups (Orange): AQI 101-150

The general public is unlikely to be affected, but more sensitive individuals may experience health effects. - Unhealthy (Red): AQI 151-200

Everyone may begin to experience health effects. More serious health effects may be seen in more sensitive individuals. - Very Unhealthy (Purple): AQI 201-300

Everyone is likely to be affected, with health warnings of emergency conditions. - Hazardous (Maroon): AQI 301-500

Health alert: everyone may experience more serious health effects.

What does the AQI measure?

The AQI measures for five key pollutants:

- Fine particulate matter

- Ozone

- Carbon monoxide

- Sulfur dioxide

- Nitrogen dioxide.

There’s no doubt that these all matter when it comes to health and safety. The trouble is, the AQI doesn’t measure toxic gases that form when buildings and other structures burn at high temperatures.

So far, estimates suggest that more than 12,000 structures have burned in the LA wildfires. The composition of these buildings and their contents is largely unknown. This is why some scientists and local residents are wondering whether the AQI is up to the task of credibly assessing air quality in this moment.

The Air Quality Index that says the air is safe in LA after the wildfires. The AQI does not take into account toxic gases that form when urban materials burn at such high temps. My team and I are discussing going there to measure the toxins in the air (and between SD and LA).

— Kimberly Prather, Ph.D. (@kprather88) January 16, 2025

What’s in the air after wildfires?

We can’t know for sure what’s in the air without measuring it, but the wildfires may have polluted the air in Los Angeles and nearby areas with a range of toxic substances.

Most wildfires burn largely trees and vegetation, which creates some troubling air pollutants. The scientific consensus, though, is that homes and other structures kick out far more and more troubling pollutants when they burn. This is because buildings contain a huge number of synthetic materials in couches, mattresses, wiring, tiling, flooring, and whatever else is hanging around in garages and sheds.

Yet another reason why it’s far better to choose natural materials for home furnishings and renovations.

The LA wildfires affected homes, vehicles, industrial sites, and other structures. The result is a potentially toxic slew of gases, particulate matter, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

Potential air pollutants in LA after the fires included:

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Potentially carcinogenic | Can cause blood and liver disorders | Much higher concentrations in urban versus forest fire smoke |

| Benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes (BTEX) | Toxic organic compounds | Linked to cancer and autoimmune disorders | Elevated levels in urban fire smoke |

| Dioxins and furans | Hormone disruptors that can affect fertility | Carcinogenic | Significantly higher levels in urban versus forest fire smoke |

| Phosgene | Highly toxic gas | Severe lung damage and respiratory failure | Comes from burning plastic |

| Heavy metals | Toxic metals such as lead, chromium, cadmium, and arsenic | Adversely affect the brain, liver, kidneys, lungs, and skin | Much higher concentrations in urban fire smoke |

| Hydrogen cyanide | Highly toxic compound | Released when synthetic materials burn | |

| Formaldehyde | Known carcinogen | Released from burning building materials and furniture | |

| Isocyanates | Acutely toxic substances | Found commonly in polyfoam products (like foam mattresses and couches) | Released from burning synthetic materials |

| Hydrogen chloride and hydrogen fluoride | Corrosive gases | Emitted by burning building materials | |

| Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) | Many different health effects, depending on the chemical | Can be carcinogenic, neurotoxic, and affect respiratory and reproductive function, etc. | Can include styrene, released from burning plastics and synthetic materials |

In combination, these air pollutants may significantly raise the risk of heart attacks, stroke, and serious lung damage. They may also increase the risk of various cancers and developmental conditions, as well as affecting longer term cognitive health.

Many of the effects of exposure to urban fire smoke aren’t seen until years or even decades later.

How long will it take for the air to clear?

The short answer is that we don’t know for sure. Air quality depends on a range of factors, including temperature, wind direction and speed, rain, and so on. Since some wildfires continue to burn, and others will likely start, this is also an ongoing challenge rather than an isolated one.

The ash and rubble in the burned areas could continue to kick up toxic dust for years to come.

It’s readily apparent to anyone living in LA that the air quality has already improved greatly since the fires were brought under control. However, the blue skies and sunshine don’t necessarily mean ‘clear’ skies with safe air. Sure, the smoky haze has gone, but that’s just one type of air pollution.

Clean-up efforts may also inadvertently disperse pollutants into the air again, as can changing winds and any residual smoldering.

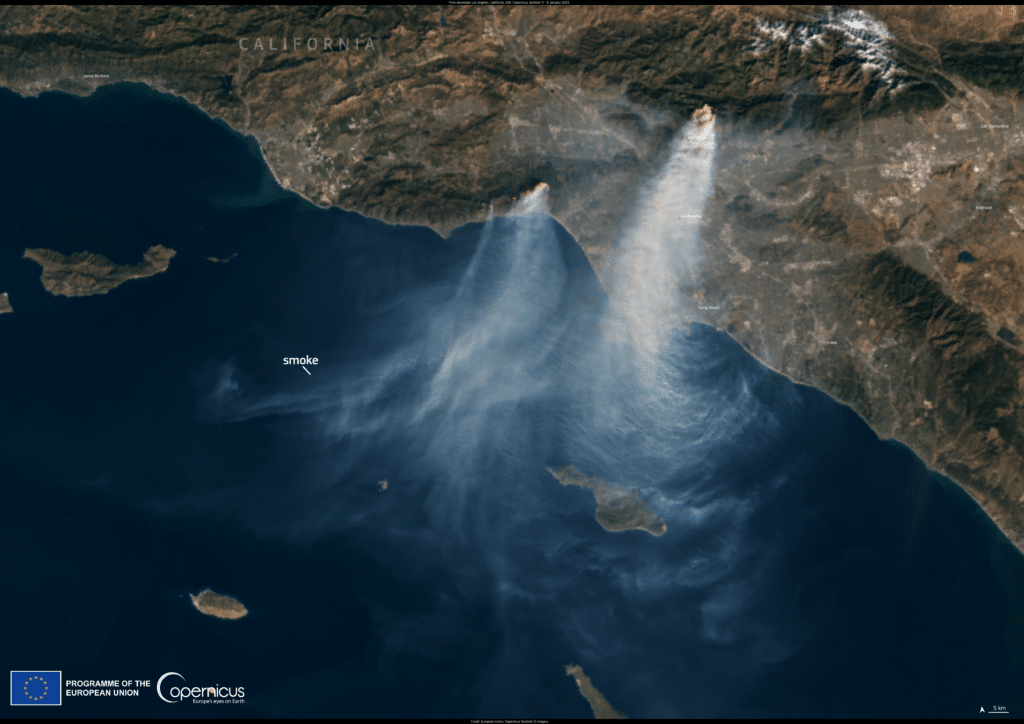

The good news in LA is that while the strong winds helped spread the fire, they also helped to blow much of the smoke out across the ocean and away from land.

What’s a safe distance from wildfires?

I live in BC, where wildfires nearby and in the interior of the province affect air quality most summers. Wildfires in Canada’s central and eastern provinces also have an effect on air quality on the west coast.

This all goes to show that there is no universal safe distance from a wildfire’s impact on air quality. Wind patterns are the major factor in how pollutants spread in the air.

Even areas where the AQI is good can be affected by pollutants that aren’t visible to the naked eye or measured using traditional metrics.

More monitoring and research

From what we know so far, the current AQI is insufficient for LA residents’ needs.

Continuing to rely on the AQI creates a false sense of security over the healthiness of the air after these significant wildfires.

Researchers such as Doctor Kimberly Prather, PhD, have said that they plan to conduct more comprehensive air quality studies. These would involve going to LA to measure air pollutants not typically monitored through the AQI.

Such research, and any protocols and tools established as a result, would be invaluable for residents looking to make more informed decisions about outdoor activities and their health. This might take the form of an independent post-wildfire air quality service, for instance, or may be something under the AQI and activated on an as-needed basis.

How this research and implementation is funded remains to be seen. Concerned residents in LA, San Diego, and other wildfire prone areas in the U.S. may want to lobby their state legislators to provide funding and oversight.

What can you do in the meantime?

The AQI is still useful, if only as a general indicator of air quality from common concerns.

The problem is that wildfires and other localized hazards require more localized, timely, and specific data on other pollutants.

The best approach may be to use data from the PurpleAir network, which comes from small sensors people install themselves. The sensors measure fine particles in the air, at a hyperlocal level. The network then uses the data to create more nuanced air quality scores. These sensors are less accurate than the EPA monitoring stations but they update far more frequently and are present in greater numbers.

PurpleAir updates every two minutes, and there are thousands of sensors in LA. They don’t tell us what exactly is in the air, but the overall score can give a more localized, and up-to-date measure of air quality.

The other option is to use a personal air quality monitor at home and a portable one when out and about.

Finally, along with wearing an N95 mask outside, running a good air purifier inside can help ease symptoms after unavoidable exposure to poor outdoor and indoor air.